Resource Review: Disappearing Tricks

First in a planned series of reviews of resources used for past episodes. This entry highlights Dr. Matthew Solomon’s excellent book Disappearing Tricks: Silent Film, Houdini, and the New Magic of the Twentieth Century (University of Illinois Press).

Teaching myself about film comedy history involves more than just watching movies, which I love to do. Fortunately for me, I also love reading nonfiction and this project has opened up a whole new library of titles and authors to explore. I’m lucky enough that I’m also getting an opportunity to interview some of the authors of the resources I’m using for the Acting Funny project. So, from time to time here on the blog, I will share a quick review for you of a resource I used for a recent episode. See my disclosures page for comments on my review policy.

When movie magic was real magic.

Dr. Matthew Solomon’s excellent history of the relationship between stage magic and early cinema, Disappearing Tricks: Silent Film, Houdini, and the New Magic of the Twentieth Century, was featured in Season 01, Episode 02: “Who were the early adopters of film and comedy? (1896)”

I grew up as a kid in the 1970s in what turned out to be something of a golden age for magicians on television. There were magicians on Saturday morning TV. There were magicians with variety show specials. There were magicians performing on late night television. You could see other less magical celebrities try their hand at stage magic on proto-reality shows such as Circus of the Stars. There were mentalists, illusionists, sleight of hand tricksters, and hypnotists. Before I was 10 years old, I probably had seen hundreds of ladies sawed in half from the comfort of my living room sofa. And it never grew old.

I knew their names: Henning, Blackstone Jr., Copperfield, among others. But one name stood out from the rest, and I never saw him perform even once. Yet, if I heard anyone mention the name Houdini, I stopped whatever I was doing and stayed in front of the screen. Never mind that Harry Houdini had been dead for more than forty years before I was even born. I knew his legend. I knew his story- or at least as much as a 10-year-old kid in the late 70s could know about a star performer of vaudeville. And if someone was going to even talk about Houdini, much less attempt to do one of his famous tricks, I was all in.

Some forty years later, when I embarked on this project to learn about the history of film comedy, I was delighted to see my early love of magic and magicians return to me in an unexpected way.

As I started to learn about the life of Georges Méliès and his role in the early days of film, I began to pick up on the thread that magicians and people like Méliès who inhabited the world of stage magic, were key players in the earliest days of film’s emergence. That realization led me to Dr. Matthew Solomon and his book, Disappearing Tricks: Silent Film, Houdini, and the New Magic of the Twentieth Century.

While Dr. Solomon’s book title name drops the great Harry Houdini, this book is just as much- and rightfully so- about the work and legacy of film pioneer Georges Méliès. Solomon’s thorough research also brings to light names and contributions of other magicians from the late 19th and early 20th century who played an important role in the intertwined evolving histories of stage magic and cinema.

Solomon’s work begins with a look at the emergence of spiritualism in the Victorian era and that era’s ongoing fascination with death and the hereafter. Intriguingly, the author illustrates how the world of magicians coalesced around the notion of exposing fraudulent behavior from con artists posing as psychics, mediums, and others. This effort at anti-spiritualism would inform the design of new tricks and new evolutions in stage magic performance. As Solomon illustrates, these new techniques and performances would also find their way into early film narratives of the 1890s.

This introduction to the competition between magicians and spiritualists was fascinating to read and helped me better understand the context of the history I would witness in early films. Solomon’s book then takes us on a journey through the parallel timelines of Méliès and Houdini in France and the USA, as they learn to adapt to and embrace the emerging technology of cinema as a component of or complement to their performances, up to Houdini’s own appearances in films in the teens and twenties.

Disappearing Tricks was crucial to me in researching the 1896 episode, and remains a resource I refer to as I continue to move forward in time to the early 20th century. And, while academic in nature, the book itself is an enjoyable read with Solomon developing a logical narrative to tie together the various key achievements and personalities. I would happily recommend this book to anyone who enjoys reading histories in general, but especially to anyone with an interest in early film history, magic and vaudeville history, and pop culture history, as it will certainly illuminate new connections for the reader on how those three areas overlap so easily at the beginning of the 20th century. It also includes a comprehensive bibliography to help you track down other potential resources to explore and, a favorite feature of mine in any book like this, an excellent index to help me find a specific topic or personality I want to easily access for future reference in my own research.

Disappearing Tricks: Silent Film, Houdini, and the New Magic of the Twentieth Century was originally published in 2010 by the University of Illinois Press. It received the Best Moving Image Book Award from the Kraszna-Krausz Foundation in 2011, and was also named a Choice Outstanding Academic Title in 2011 by the Association of College and Research Libraries. Dr. Solomon is an associate professor in the Department of Film, Television, and Media at the University of Michigan. He is currently working on a book about Georges Méliès.

Film Comedy As Family Business: George Albert Smith & Laura Bayley

Film is a collaborative effort. Even when one person gets the credit, there are usually more people involved. In this post, we look at an early husband-and-wife team from the 1890s, who are only just now beginning to be recognized as a true creative partnership.

I was interviewing a husband-and-wife filmmaking team this week for an upcoming pair of episodes for the podcast. Catherine Dee Holly and Fray Forde work together in Los Angeles as COKI Productions where they have produced and acted in some wonderful short films. We were talking about a pair of husband-and-wife filmmakers from the late 19th century who will be featured in the 1897- and 1898-themed episodes.

“Did it surprise you,” I asked, “when I shared with you the information about these couples?”

Fray answered, “No. Not really. Filmmaking has always been about collaboration. There’s always someone else working with you. Even if only one person is getting the credit, they didn’t do it alone.”

And I think that sums up the story of some of our early film pioneers very nicely. One of the things I’ve noticed in my project to teach myself the history of film comedy from 1895 to the present day is that a great deal of attention is often paid to specific individuals with passing notice (if any) given to the supporting cast who worked with the person in the spotlight. And, I think this is especially true when the team happens to be a married couple. It isn’t terribly shocking or surprising that most of the attention is often focused on the husband, given the culture these couples worked in and even the culture we live in now. Happily, in my interviews with film historians about George Albert Smith and Robert W. Paul, both historians were quick to point out to me their belief that the wives of these gentlemen were overdue for credit of their own as full creative partners in the pioneering of film and film comedy.

With this blog entry, I want to highlight one of these couples as a sneak preview of the upcoming episodes. Perhaps it will spawn an irregular series here on some of the hidden figures who have helped build the history I’m now so happily exploring. In this post, I’m going to give a quick introduction to a most fascinating pair of film pioneers: George Albert and Laura Bayley Smith.

George Albert Smith (1864-1959) and Laura Bayley (1862-1938)

Husband and wife film pioneers George A. Smith and Laura Bayley are pictured here in a scene from A Kiss in the Tunnel (dir. George A. Smith, 1899).

I’m only a few “years” into this project, but George Albert Smith and his wife Laura Bayley have easily been my favorite new-to-me discovery so far. I find that I am loving the back story of this couple as much as I’m loving their surviving films.

I was fortunate to interview film historian Frank Gray, principal lecturer at the University of Brighton’s School of Media, on the history of Albert and Laura. Gray is the author of The Brighton School and the Birth of British Film*, one of my resources for the episode and this post.

Laura Bayley was born in the English seaside town of Ramsgate in 1864 as the third of four sisters. Laura’s older sisters, Eva and Florence, began a stage career as singers around 1871 with Laura and her little sister Blanche joining the family musical group by 1873. The Bayley Sisters developed a fine career touring and performing to venues throughout southeastern England as part of a revue featuring songs, sketches, magic lantern displays, dramatic readings, and other entertainments. In addition to singing, Laura also took on many of the lead acting roles associated with the family troupe’s performances at annual British pantomimes during the Christmas holidays in the 1880s, including roles as Cinderella, and as the “Principal Boy” (a pantomime tradition of a young woman playing the role of the male protagonist) in pantomimes such as Robinson Crusoe, Robin Hood, and Aladdin. While performing musical sketches as one of the “little misses Bayley” and through her years as a lead actress in pantomimes and other performances, Laura had been establishing herself as a multi-talented comedienne.

In 1887, the Pier Pavilion in Hastings hosted a show in celebration of the careers of the Bayley Sisters, featuring guest performances from all sorts of variety entertainers. One of the performers at the benefit/tribute show, was a young man named George Albert Smith.

Britain’s first great film comedian?

Laura Bayley in a scene from Mary Jane’s Mishap (dir: George Albert Smith), 1903.

George Albert Smith was born in 1864 in East London. By 1881 at the age of 17 he is living with his mother and three sisters in Ramsgate, the Bayley Sister’s hometown. This area of England is known for a string of sea coast towns built around the tourist economy. The towns, primarily Brighton, were a short train ride from London and provided tourists with all manner of entertaining distractions such as pleasure gardens (think of them as something like a Victorian-era amusement park), aquariums, music halls, museums and halls of curiosities, lecture halls, and more. He quickly joined in with this tourist/entertainment economy, taking to the stage at the age of 18 as a “mesmerist” and “thought reader.”

He was soon providing lectures and demonstrations of mesmerism on the sea coast entertainment circuit. Learning that Smith was a Victorian-era mesmerist delighted me for several reasons, notably that it puts him squarely inside the world of stage magic and spiritualism. If you’ve listened to the podcast’s second episode [Who were the early adopters of film and comedy? (1896)], you already know that the inhabitants of this world were some of the earliest users of film technology. (And if you haven’t already listened to the episode, I hope you will.)

His success as a performer earned him an invitation to perform at a variety show tribute to the Bayley Sisters in 1887 in Hastings. I don’t know if this was the first time Smith and the Bayleys had met. It seems like they should likely have crossed paths while performing before then, but Frank Gray points out in his book that this is the first time the two performers are mentioned together in the press. A year later, Albert Smith and Laura Bayley would be married, and their careers would soon take on a new trajectory.

The mesmerizing George Albert Smith

One of the pioneers of British cinema and film comedy

As Laura and her sisters, under management from one of Laura’s brothers-in-law, would continue to perform at music halls and other venues in the late 1880s/early 1890s, Smith pivoted away from mesmerism and hypnotism shows toward becoming a magic lantern projectionist and lecturer. (Not coincidentally, you can learn a little historical background on magic lanterns and English music halls in Acting Funny’s third episode.)

Smith and Bayley soon became the managers of a pleasure garden in Hove, England, near Brighton. The garden was home to a mineral spa, wooded parkland, picnic areas, and host to all sorts of entertainments including tightrope walkers, open air theatrical performances, parachuting demonstrations, educational lectures, demonstrations of Edison’s phonograph machine, comedy revues, afternoon teas, children’s activities, a monkey house, fortune tellers, magic lantern shows, and more.

Smith had become quite skilled at presenting magic lantern entertainments and in 1896 he added a new technology to his skill set when he began demonstrating film projectors and assembling a small program of films to show curious audiences. By 1897, he had converted a building on the pleasure garden grounds to a darkroom for film development and entered the filmmaking business on his own.

What’s interesting about Smith is that when he sets up his new film company, he promotes it immediately as a company specializing in comedy films. It seems an odd thing to do in 1897, as almost no one who is making films is specializing in anything really at this point. Most everyone is making a mish-mash of films across a wide range of genres from documentary to comedy, early horror and science fiction, fairy tales, dance demonstrations, nature scenes, travelogues, and whatever else a cameraman could manage to capture on 40-60 seconds of film reel. I believe this is where Laura’s influence can first be seen in their creative partnership. Laura from her work on-stage and in entertainment business, would know that specializing in a genre is an effective way to build a loyal audience and, not coincidentally, her particular genre was comedy.

Laura also had many connections in the performance world, particularly again among comedians, and this allowed Smith to build a cast of regular performers for his early movies. This included most frequently Laura herself, but also included comedians such as Tom Green who often appears on screen as Laura’s husband or suitor. In fact, some of the notes in Smith’s cash ledger suggest that Laura may have been the uncredited director of some films that are currently credited to her husband. An example of this would be Comic Face, an 1897 short film featuring Tom Green drinking a beer and making a series of funny faces for the camera as his character gets progressively inebriated (the film is also known as Old Man Drinking a Glass of Beer).

While Laura was often on screen, she was also busy behind the camera, too. She is known to have been the cinematographer for some of Smith’s films, particularly those using the Biokam, a camera/projector/printer combination created by Smith and other business partners designed for home and personal use in the late 1890s and early 1900s— well before we all thought we had become cinema auteurs with the advent of the home camcorder in the 1980s.

Smith’s films make use of his talents learned as a magic lanternist, where he grasps the possibility of lantern tricks such as dissolves and quick change jump cut-style animations as potential additions to the cinematic language. His early films are notable in their use of multiple scenes at a time when many filmmakers were still producing single-scene films staged in front of the camera as if for a photograph or stage production.

One of these films, The X-Rays (aka The X-Ray Fiends) from 1897, is going to be Acting Funny’s featured film for podcast episode #4, which is set to debut on Monday, February 15. In the film, you will find Smith has put together a film with three scenes by using jump cuts to pull off an early special effect sequence meant to poke fun at a brand new technology: x-rays. In this episode, we will talk at length about George Albert Smith and Laura Bayley with guest expert Frank Gray from the University of Brighton. We’ll also revisit Laura and George in our 1903-themed episode with a conversation with film historian Maggie Hennefeld on women in early film comedy, featuring the film Mary Jane’s Mishap later this spring.

Some additional recommended reading on Laura Bayley can be found on the Women Film Pioneers Project.

I hope you’ve enjoyed learning a little bit about one of my new favorite families in film comedy: Laura Bayley and George Albert Smith. If you aren’t already listening to Acting Funny, the podcast that takes film comedy seriously, and my quest to teach myself the history of film comedy one year at a time, from 1895 to the present, please do take a moment to like, follow, or subscribe to the podcast on your favorite podcast listening service. You can find a listing of available sites on the Where to Listen page, or you can also find episode descriptions and embedded podcast players on each episode’s entry in the Episodes section of this site.

If you want to be updated once a month on future topics and guests, please feel free to subscribe to The Banana Peel, the free monthly newsletter for Acting Funny. You can find a subscription form on the bottom of any page on this site. Thanks for reading and listening!

This blog post is part of the Home Sweet Home Blogathon hosted by Realweegiemidget Reviews and Taking Up Room.

* Acting Funny and Shane Rhyne are participants in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. This site only recommends products or services I use personally or are directly related to the subject of my podcast episodes and blog posts. While I do accept review copies, all books, films and other products or services reviewed were purchased by me through normal retail channels unless otherwise noted.

I was provided a digital review copy of The Brighton School and the Birth of British Film by the author.

Schedule Changes

As usual, I find myself at work with the clock as my enemy.

When I first announced the creation of Acting Funny, I announced it as a weekly podcast. Well, actually, that’s not entirely true. When I first envisioned the podcast I had the insane idea that I would make it a DAILY podcast covering 125 films in 125 days. Fortunately, sanity prevailed and I scaled back that plan to a weekly format.

However, the sharp-eyed among you have doubtlessly noted that more than one week has passed between the launch of Episode 01 and the publication of Episode 02. That’s my fault. My sound editing skills for a podcast need some serious work and I made some notable errors in the editing process. Enough so that I’ve recruited assistance moving forward to help me undo my mistakes and to help me get the quality of the podcast up to the level I believe it deserves. It will take some time to get things back on track again, but I appreciate your patience. It may also take a few more episodes to get to a point where a lot of my past mistakes are truly in the past, so bear with me and don’t blame the new guy. (By the way, the new guy is my oldest son, Kyle. He is graduating soon with a degree in media and communications and I’m grateful to have him on board as a new partner in this. He’s very patient with the old man, too.)

So, moving forward, I’ve decided that Season 01 will be a bi-weekly podcast with new episodes dropping every other Monday. This will give Kyle and me time to work out the kinks and get the sound quality up to where it needs to be. That means, Episode 03 is now scheduled to drop on February 1, with additional episodes coming out on February 15, March 1, and March 15, and so on.

If you haven’t already, you can subscribe to the podcast newsletter, The Banana Peel, to get monthly updates on the episodes scheduled for future dates with news about guests, topics, and more. I hope you enjoy the new episodes and thanks for listening!

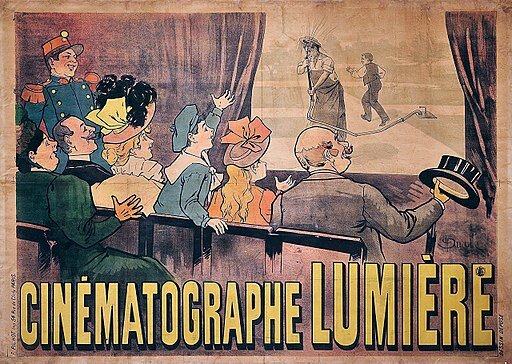

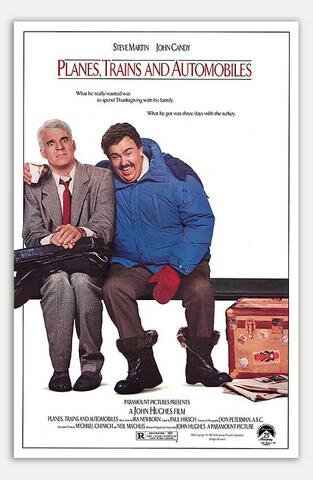

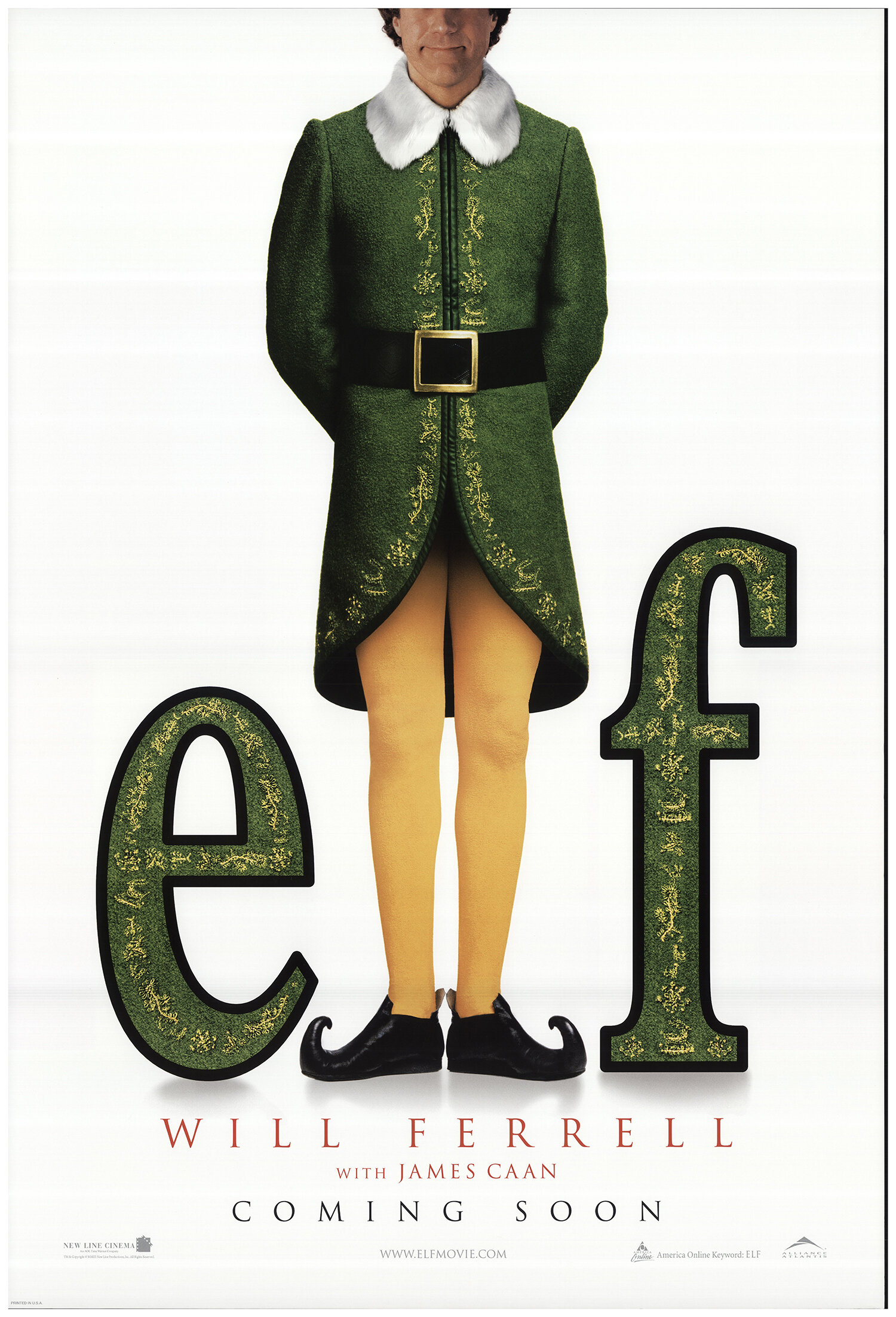

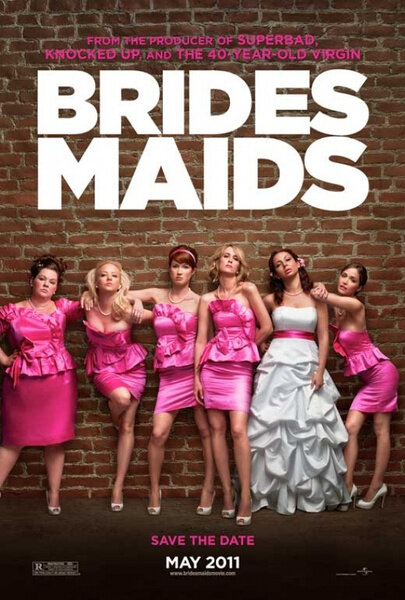

Comedy Movie Posters

As I mentioned in the 1895 episode, an interesting bit of trivia about the first comedy film, L'Arroseur Arrosé (The Sprinkler Sprinkled), relates to its movie poster. It marked the first time a movie poster showed a scene from the film on the poster, as it depicted the audience laughing with delight as the young brat scampers away from the soaked gardener. Although, really, the artist should have asked those ladies in the front row to take off their hats. Can you imagine having a ticket to the first cinema exhibition and sitting behind those hats? I’d want my franc back.

Image: Cinematographe Lumière poster from 1895 exhibition. Marcellin Auzolle (1862-1942), via Wikimedia Commons

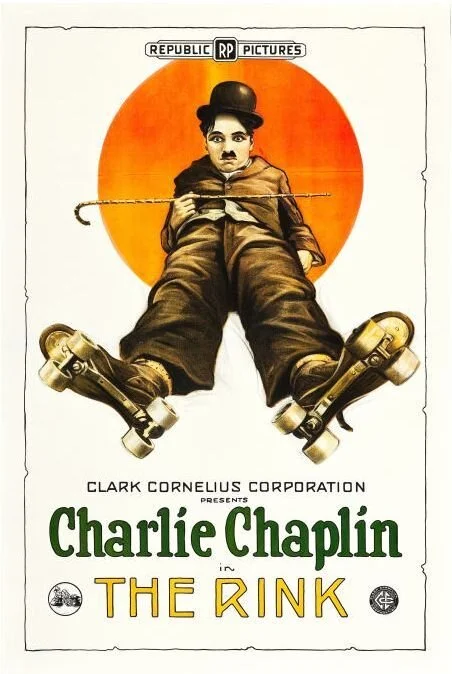

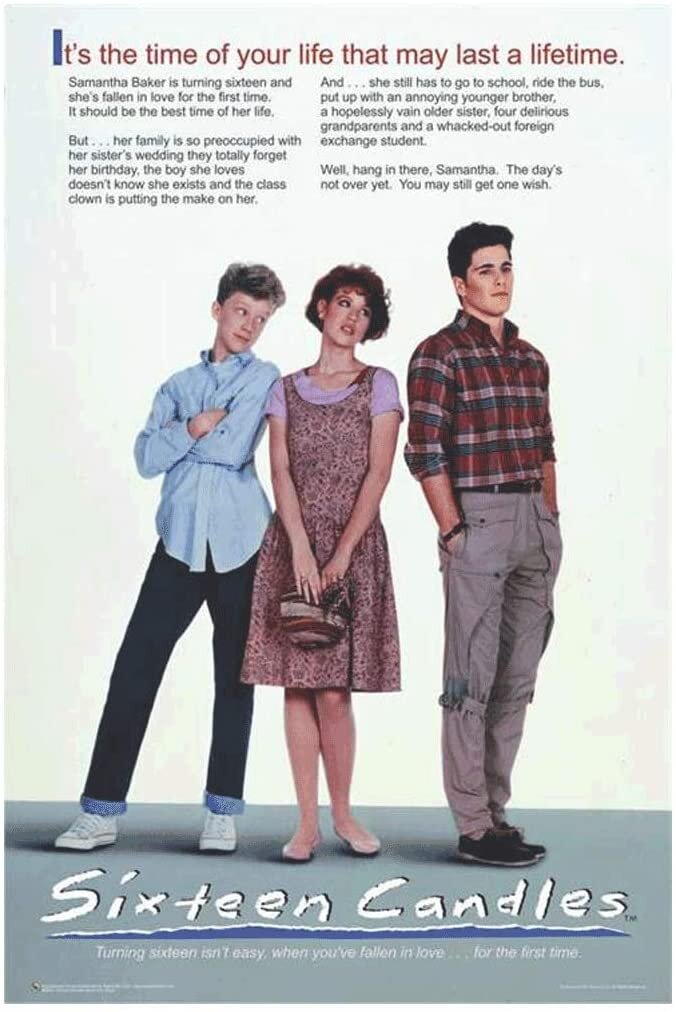

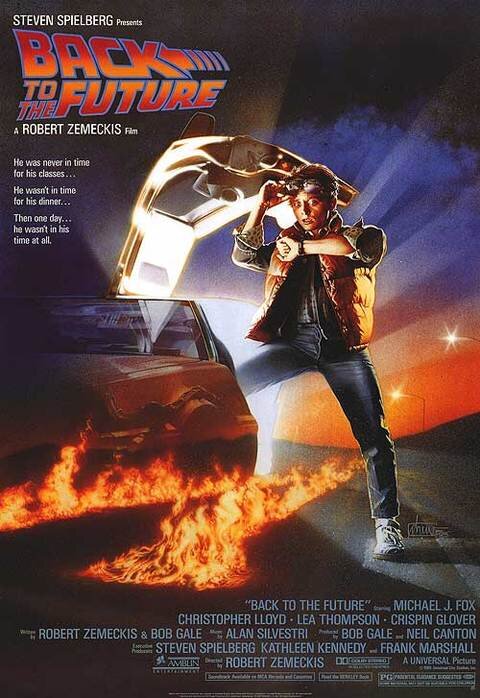

It got me to thinking about some of my favorite movie posters from comedy films over the years and I thought I’d share a few of my favorites here.

What are some of your favorite comedy movie posters? Do you remember any that helped convince you to definitely see the movie?

The Rules of the Game

125 films. 125 episodes. 125 years. It seems like a simple concept, but it turns out I have questions. Maybe you do, too. Here are some starting answers.

125 comedy movies covering 125 years of film history. One movie per year. One year per episode.

On the face of it, it seemed simple enough. But, I soon began to realize I needed to create a more defined playing field. This would be for the sake of my own sanity, if nothing else, and to hopefully anticipate some potential listener questions/concerns. It would make sense if these are indeed frequently asked questions from new arrivals to this project because they are the very questions that first jumped to my mind when I began drafting the idea. Here goes:

WHAT QUALIFIES AS A COMEDY?

For the most part, I’m going to be pretty liberal on this, but if most of the reference sources and critics identify the movie’s genre as a comedy or some sort of comedy hybrid (e.g., action comedy, comedy-drama, dark comedy, comedy-sci fi, etc.), I’ll consider it. And, humor is often an important device found in other genres (action and horror, for example), but that doesn’t necessarily mean that every action film or horror film is also a comedy, even if the hero has a lot of great one-liners throughout. I’m going to have to take the “I’ll know it when I see it” approach. For me, the main question will be: is comedy one of the primary intents of the creator or just a means of relieving tension (thus, comic relief) from what is otherwise a very fine thriller/action film/western/slasher flick.

WHAT ABOUT ANIMATED COMEDIES?

I have decided, for better or worse, to not include animation in this 125-year run of films. Not because they aren’t good comedies, in fact they’ve represented some amazing comedies over the years, but I really wanted to focus on live-action comedy. That doesn’t mean animation won’t be discussed at various points in the conversations, but it will be unlikely that a purely animated film would be the featured movie of a future episode.

IS THIS AN ATTEMPT TO CREATE A “TOP 125 COMEDIES OF ALL TIME” LIST?

Dear Lord, no. That would be madness. This isn’t even an attempt to identify the top comedy/best comedy/most influential comedy, etc., of any given year. The films I end up choosing to feature in their given years are most likely to be reflective of a theme or topic that I want to discuss in the evolution of comedy. This might mean that we’ll be looking at a particular film because I think it is a good representation of the work of a person I want to discuss in depth (writer, director, actor, etc.), or because it represents something going on in the zeitgeist of its era, or it represents an innovation in the way comedy and/or film is presented, or any number of reasons. I can’t promise that every film will be the best comedy film of its year. I can’t even realistically promise that some of the films will be very good at all. There may very well be a few stinkers in the bunch, or films whose messaging has not held up well over time. But, it’s also likely that is the reason I chose it for that episode, because it’s a good conversation to have sometimes.

ARE YOU ONLY LOOKING AT AMERICAN FILMS?

Nope. Comedy film got its start in France and has always been an international creation. While I acknowledge that Hollywood contributes a significant amount of output, I am interested to see how other cultures have tackled the issue of putting comedy on film and how that has all filtered down to today’s world over time. So, I hope that amongst the 125 films to be discussed we’ll get an opportunity to leave Hollywood from time to time to see what was/is happening around the world.

SO, IS THIS JUST A MOVIE REVIEW PODCAST OR A PODCAST WHERE YOU RIFF ON A MOVIE?

No. While there will likely be some amount of brief review and synopsis of the film at the beginning of the discussion, to help people who have not seen the film, this is really not intended as strictly a movie review podcast. How do you even do a review of a 40-second film from 1895 that isn’t 10 times longer than the movie itself? And, no we won’t be riffing on the movie or otherwise watching the movie during the episode. We’ll have watched the episode (separately most likely given the current conditions) and then having a conversation revolving around that film and related topics during the episode.

WHO IS THIS “WE” THAT YOU KEEP MENTIONING?

I’ll be hosting the episodes and getting the conversation started, but to have a conversation, I’ll need guests. My hope is you’ll get to hear me in conversations with people in a position to help teach me about the things I’m curious about, namely: how comedy films have evolved over time, who helped shape those evolutions, and what those films have to teach us about our past, present, and possibly future. I’m reaching out to a number of guests, including people in the worlds of cinema studies, film collectors and archivists, critics, filmmakers, historians, pop culture experts, niche topic experts, and more. I’m also inviting guests to be a part of the conversation from the world of comedy. These might include improvisational performers, stand-ups, musical comedians, comedy writers across various media, and more.

—-

I think that pretty well covers it for now and hopefully it gives you a better sense of what I’m trying to do. I hope you’ll subscribe to the Acting Funny podcast when it debuts later this year and, in the meantime, hope you’ll subscribe to the newsletter (link in the footer below and elsewhere on the website) to get updates on when the podcast is debuting, where you’ll be able to listen to it, announcement of guests, and more. Thanks!

If you missed the first blog post introducing myself and the whole Acting Funny concept, feel free to read “Why I’m Taking Comedy Films Seriously” when you have a moment.

Why I’m Taking Comedy Films Seriously

I’m launching a podcast about the history of comedy films. So, why me? Why this topic? What’s it all about? Do we need this?

Look, I get it. Starting a podcast in 2020 about the history of comedy films might come across as a bit tone deaf, given that the news for much of this year has delivered seemingly nothing but anxiety, tragedy, injustice, and absurdity at a breakneck pace. And that’s just any random Tuesday.

But, perhaps that’s the best time to turn to comedy. Not merely as an escape from the daily stresses, although it admirably serves that purpose, but also because comedy can be a useful tool to help us understand the world we inhabit. At least, that’s the basis of the question I asked myself that inspired this podcast: what can learning the history of comedy films teach me about comedy, about film, and about who we are? And, as I’ll illustrate in a moment, that’s the sort of question I love to ask myself about nearly any bit of pop culture or history that captures my attention for an extended moment of time.

While the question sounds academic in nature, let me take this moment to point out that I am not an academic (but I am a big fan of such and hope to convince actual academics to join me as guests in these conversations). I am not an expert in any capacity on any of this. I don’t hold any degrees in film studies or related topics (although I did take a very enjoyable Intro to Film Studies elective many decades ago in my sophomore year of college). In fact, I don’t hold any degrees at all. And, while I have a great love of comedy films, I know that my knowledge of their history and evolution is superficial at best: trivial facts filled in by random biographies and essays I may have read here or there and bits of info gleaned from the hosts of Turner Classic Movies as they introduced the next film of the day’s schedule. That’s more or less the point, though. I want to teach myself whatever I can learn that will take me beyond merely knowing the household names (Chaplin, Keaton, the Marx Brothers, Mel Brooks, etc.) and gaining a better understanding of how the people who made us laugh in the past have influenced what makes us laugh today.

And so, when the pandemic gave me some unexpected free time by putting an end to my nights of driving around the Southeastern US performing stand-up comedy in bars, breweries, comedy theaters, festivals, and at least one vacant lot, I reached into the back of my mind where this question about comedy film history had been fermenting and decided to act upon it. I got my hands on some cinema studies textbooks. I found essays on the early film pioneers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. I followed YouTube rabbit holes of old movies and discovered online collections maintained by the Library of Congress and other libraries, museums, and archives. As I became more fascinated by what I was learning, I realized that perhaps other people might enjoy it, too.

I’ve kind of done something like this before, to be honest. Something in my wiring leads me to it. Since my childhood, when I have found a topic that really captures my interest, I usually have come to a point when I want to learn as much as possible what led to the genesis of that topic. My mother introduced me to Elvis Presley’s music when I was very young. And when I got old enough to get my own records, I wanted to learn more about how his sound came to be. Soon, with the help of a trusty library card and some spare change earned from a newspaper route, I was getting my hands regularly on LPs containing rockabilly, rhythm and blues, and then blues, before working my way forward again chronologically. Before I knew it, I was the kid in middle school with a weird knowledge of jazz and big band music, whose record collection hopscotched among musical selections bound to no single decade or genre. When I found a favorite author, I would usually ask a teacher who that author liked and then set about reading those works, too. In the 1990s, I found myself working for a regional historical society, and soon realized my odd way of deconstructing a topic of interest worked quite nicely as a means of using pop culture topics to teach public history. Living in the football-mad southeastern US, I took an interest in the history of college football and used that to curate a museum exhibit and lecture series on how the history of college football both reflected and played a role in shaping the culture of East Tennessee. (The exhibit and lecture series were called “The Spirit of the Hill: Football in the Culture of East Tennessee.”) My favorite such project was the creation of a self-guided walking tour of downtown Knoxville, that played upon my interests in regional history, music history, and my previous professional experience in radio, to highlight Knoxville’s role in the development of country music. (If you’re ever in Knoxville, the Cradle of Country Music Walking Tour is still there waiting for you to enjoy.) I loved the opportunity to dive backwards in time and to find ways to share what I had learned myself.

Which brings us all back to this. As a comedian (by the way, you’ve never heard of me and that’s alright as I’m pretty low on the scale of comedians, but you can go to my comedy website to learn more about that part of my life), I was quite aware of podcasts, but had mostly resisted the urge to create one. But podcasting seemed an ideal medium for me to share this. And once I realized that 2020 was the 125th anniversary of the first comedy film’s first public screening, I knew what I wanted to do. So, Acting Funny, was born (with some great assistance from my wife in helping me choose a name). Each episode will look at one year, moving in chronological order from 1895 forward, focusing on one film from that year. I’m inviting guest experts to join me each episode for a discussion of that film and that year, to see what I (and you) can learn about how comedy and film have helped us move forward.

So, that’s the plan at least. And, this post hopefully explains a bit about me and why I wanted to do this. In the next post, I’ll explain more of the “ground rules” of how I hope to keep this thing on the tracks. Thanks for reading this far if you did. I hope you’ll stick around and be a part of the launch this December for the first episode. If you haven’t already, please subscribe to the newsletter (you’ll find a submission form at the bottom of this page) where you can find out when I’m launching the first episode and where you can find the podcast on your device.